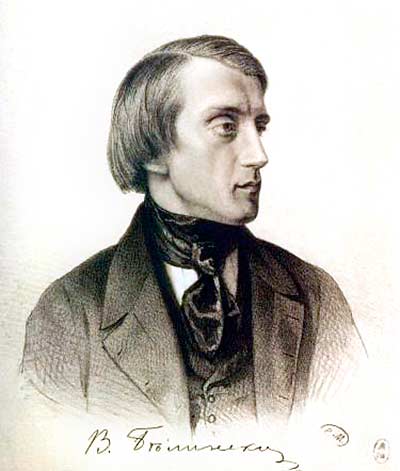

Goncharov “Zion of agony”

In his article “Zion of agony”, I. A. Goncharov begins the characterization of the comedy “Woe from Wit” (see the summary, analysis and full text) with an indication of its unusual “youthfulness, freshness” – “she, like a hundred-year old man, about of which everyone, having lived out his turn in turn, dies and falls, and he walks, vigorous and fresh, between the graves of old people and the cradles of new people. ” Although “the significance of Pushkin in the history of Russian literature was incomparably greater than that of Griboedov – he occupied with himself his whole epoch, he himself created another, gave birth to schools of artists” – nevertheless, the heroes of his works (eg, Onegin) faded, became a thing of the past . Lermontov Pechorin also outlived his time, not to mention the heroes of Fonvizin. Meanwhile, Chatsky – the image is still bright.

In his article “Zion of agony”, I. A. Goncharov begins the characterization of the comedy “Woe from Wit” (see the summary, analysis and full text) with an indication of its unusual “youthfulness, freshness” – “she, like a hundred-year old man, about of which everyone, having lived out his turn in turn, dies and falls, and he walks, vigorous and fresh, between the graves of old people and the cradles of new people. ” Although “the significance of Pushkin in the history of Russian literature was incomparably greater than that of Griboedov – he occupied with himself his whole epoch, he himself created another, gave birth to schools of artists” – nevertheless, the heroes of his works (eg, Onegin) faded, became a thing of the past . Lermontov Pechorin also outlived his time, not to mention the heroes of Fonvizin. Meanwhile, Chatsky – the image is still bright.

“Chatsky live and do not translate in society, repeating at every step, in every home … Where the old gets along with the young under one roof, where two centuries converge face to face in crowded families, there is always a struggle between fresh and outdated, sick with a healthy one, and everybody fights on miniature Famusovs and Chatsky fights, ”Goncharov says.

“Every deed requiring renewal causes Chatsky’s shadow – and no matter who the figures are, whatever the human matter they stand on, whether there will be a new idea, a step in science, in politics, in war – they won’t get away from two the main motives of the struggle – from the council “to study, looking at the older ones”, on the one hand, and from thirst to strive from the routine to the “free life”. That is why he has not grown old so far and will hardly ever grow old Griboedovsky Chatsky, and with him the whole comedy. ”

Speaking about the attitude of the Russian public to this comedy, Goncharov said that “the literate mass appreciated it in fact. Immediately realizing her beauty and not finding flaws, she smashed the manuscript to shreds, poems, half-pensions, spread all the salt and wisdom of the play in colloquial speech, turned the million directly into hryvnias and talked to Griboedovka proverbs that literally dragged the comedy to satiety.

But the play endured and this test, and not only did not become vulgar, but became, as it were, more expensive for readers, found in each of them a patron, critic and friend, like Krylov’s fables, who did not lose their literary power, moving from the book to the living speech. ”

Referring to the Russian criticism, which judged the comedy, Goncharov in “Milionne of Torments” notes that some of her judges “appreciate in her the picture of the Moscow customs of a certain era, the creation of living types and their skillful grouping. Others, giving justice to the picture of morals, fidelity of types, value the more epigrammatic salt of language, living satire, morality, which the play still, like an inexhaustible well, supplies everyone for every everyday step of life. ” Agreeing with these opinions of Russian criticism, Goncharov continues: “But even those connoisseurs and other connoisseurs almost silence the most“ comedy ”, the action, and many even deny it the cash of the stage movement [1]. The critic does not agree with this opinion.

“How is there no movement? – he exclaims, – There is – a living, continuous from the first appearance of Chatsky on the scene until his last exclamation: “Carriage for me, carriage!”

“This is a subtle, intelligent, elegant and passionate comedy, in a close, technical sense, true in fine psychological details.” Goncharov tries to prove these words with a detailed analysis of the characters.

“The main role in it is, of course, the role of Chatsky, without which there would be no comedy, but perhaps a picture of morals. Griboyedov himself attributed the grief of Chatsky to his mind, and Pushkin refused him altogether in his mind. Goncharov tries to reconcile this contradiction.

“Chatsky,” he continues, “is not only smarter than any other person, but also positively smart. His speech is full of wit, wit. He has a heart, and, moreover, he is immaculately honest. In a word, this person is not only intelligent, but also developed, with feeling, or, as his maid Lisa recommends, “sensitive and cheerful, and sharp.” Only his personal grief came not from one mind, but more from other reasons, where his mind played a passive role, and this gave Pushkin a reason to refuse him in mind. Meanwhile, Chatsky, as a person, is incomparably taller and smarter than Onegin and Pecherin of Lermontov: he is a sincere and ardent figure, and those are parasites, amazingly inscribed by great talents, as painful creatures of an outdated century. Or their time is coming to an end, and Chatsky is starting a new century – and this is all its significance and the whole “mind.”

Both Onegin and Pechorin turned out to be incapable of doing business, of playing an active role, although they both vaguely understood that everything had decayed about them. They were even “embittered,” they carried in themselves “discontent” and roamed like shadows, with “lazy boredom”. But despising the emptiness of life, the idle nobility, they gave in to him and did not dare either to fight him or to run completely. ”

Goncharov believes that Chatsky does not look like them in this: “he, apparently, was preparing seriously for the activity,“ he writes nicely, translates, ”Famousov says about him, and everyone is talking about his high mind. He, of course, traveled for a reason studied, read a lot.