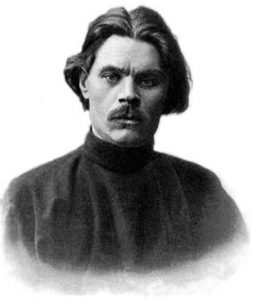

Bitter “Chelkash”

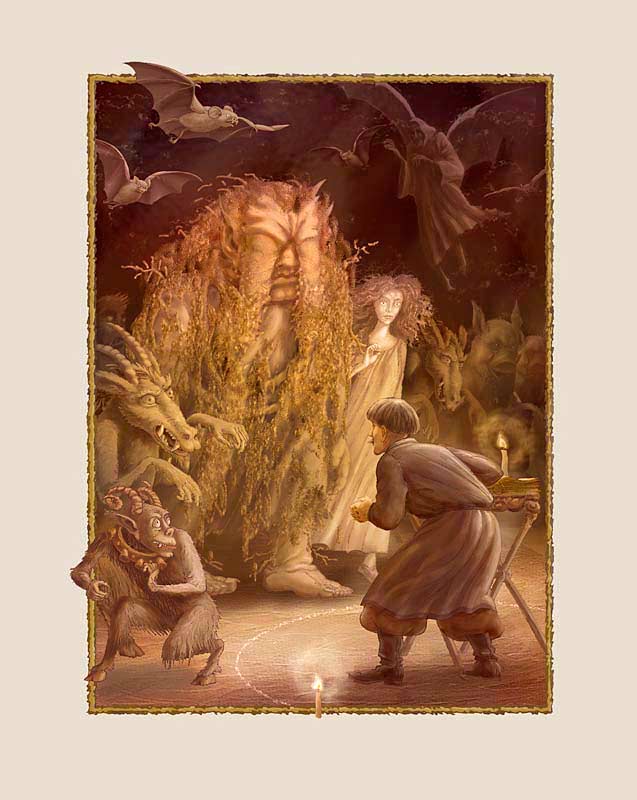

The hero of Maxim Gorky’s story “Chelkash” is Grishka Chelkash, an old wounded man, an avid drinker and a clever, courageous thief and smuggler in one of the southern Black Sea ports. Barefoot, in old, worn plush pants, in a dirty calico shirt, with a torn collar, which opened it with moving, angular, dry bones covered with brown skin, long, bony, slightly stooping, he immediately drew attention to himself by his resemblance to a steppe hawk, his with a predatory thinness and aiming gait, as smooth and calm in appearance, but internally agitated, with a sharp look, like the flight of an angry, nervous bird that he resembled.

The hero of Maxim Gorky’s story “Chelkash” is Grishka Chelkash, an old wounded man, an avid drinker and a clever, courageous thief and smuggler in one of the southern Black Sea ports. Barefoot, in old, worn plush pants, in a dirty calico shirt, with a torn collar, which opened it with moving, angular, dry bones covered with brown skin, long, bony, slightly stooping, he immediately drew attention to himself by his resemblance to a steppe hawk, his with a predatory thinness and aiming gait, as smooth and calm in appearance, but internally agitated, with a sharp look, like the flight of an angry, nervous bird that he resembled.

In the story of Gorky, Chelkash was facing a very profitable smuggling theft at night, when suddenly his friend, Bear, broke his leg, and it was difficult for Chelkash to cope with the case alone, and he unceremoniously recruited his first stranger on the street, the village guy Gavrila, who made his way home with summer earnings. The guy was broad-shouldered, stocky, and Rus, with a tanned, weathered face and with big blue eyes that looked trustingly good-naturedly. His father died, remained in the hands of his old mother; the land was exhausted, and he decided to go to his son-in-law in a good house, hoping that his father-in-law would single out his daughter. But the father-in-law did not want to allocate the lands of his daughter; Gavrila had years to be his laborer. He decided to go to the Kuban two hundred rubles to work there and get on his feet with their help; but it did not burn out. Prices for mowing in the Kuban were knocked down due to an excess of alien workers, and Gavrila had to return home almost empty-handed.

Here he met him by chance, hired Chelkash as an assistant. They rode the boat to steal a bale of silk. Gavrila rowed, and Chelkash sat on the steering wheel. The journey was full of dangers at every turn. Gavrila begged Chelkash to set him ashore. Chelkash scoffed at his cowardice, but at the same time Gavrila’s simple peasant speeches about country life brought his heart to great emotion. Gorky describes how they resurrected pictures of the distant past before Chelkash, he remembered himself a child, remembered his father, mother, saw himself as a bridegroom and saw his wife – black-eyed Anfisa, and so forth, and so on. Chelkash felt himself fanned by a gentle stream of reconciling air of his native country to his hearing, and the tender words of his mother, and the solid speeches of the primordial man-father, and many forgotten sounds, and a lot of the juicy smell of mother earth, just thawed, just plowed and just covered with emerald silk ozimi … And he felt knocked down fallen, miserable and lonely, torn out and thrown forever from the order of life in which the blood that flows in his veins developed.

These feelings touched Chelkash so much that when their business was crowned with success, Chelkash stole a few bales of silk and sold them for five hundred forty rubles that night, he gave them all to Gavrila when he rushed to him at the seaside legs and asked him to be happy by giving him at least two hundred rubles out of the money. What was the surprise and indignation of Chelkash, when Gavrila immediately confessed to him that when he returned, he fought with the idea of killing Chelkash with a paddle stroke, robbing and throwing overboard the boat. – Who supposedly missed him? And they will find – they will not try to find out: how, yes, who killed, and not the kind of person to make noise up because of him; He does not need on the ground! .. To stand for him!

Then between them a deadly struggle ensued. Chelkash rushed to Gavrila and took away his money. Gavrila threw a stone after him, severely wounded him in the head and stunned him unconsciously, but he, in his peasant good nature, was horrified by his act, and when Chelkash woke up, he began to wallow at his feet, asking for forgiveness. Chelkash called him a vile, noticing that he could not fornicate, and, with an effort, lifting his head by his hair, thrust money into his face. “Take it, take it,” he said at the same time. – No wonder he worked, tea, take it, do not be afraid! Do not be ashamed that the man almost killed! For people like me, no one will charge. Another thank you will say how to find out. On, take it; no one will know anything about your business, but the rewards are worth it. Here you go!”

Chelkash walked, staggering and still supporting his head with the palm of his left hand, and with his right hand twitching his brown mustache. Gavrila took off his wet cap from the rain, made the sign of the cross, looked at the money held in his hands, took a deep and free breath, hid it in his bosom and with wide, firm steps walked in the direction opposite to that of Chelkash.

A slave to the “social tendency” of his work, Gorky made every effort to portray in Chelkash the moral superiority of the urban tramp over the peasant. Despite the obviously improbable generosity of the criminal Chelkash, despite the fact that the laboring villager Gavrila is shown here as a traitor, half-idiot, almost subhuman, the left Russian intelligentsia met the story of Gorky with a storm of enthusiastic applause. His spirit fully corresponded to “proletarian” ideas….