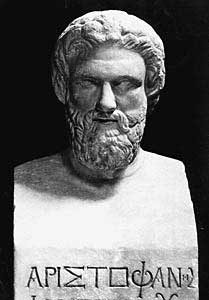

Aristophanes “Clouds”

Somewhat different from the usual carnival type of Aristophanes are his comedies, which pose problems of a non-political, but cultural order. Already the first (not come down to us) comedy by Aristophanes “Feasting” (427) was devoted to the question of the old and new upbringing and portrayed the evil effects of learning in the spirit of the new sophistic fashion. To the same topic, Aristophanes returned to the comedy “Clouds” (423), making fun of sophistry. But “Clouds”, which the author considered to be the most serious of the works he wrote so far, did not succeed with the audience and won the third prize. Subsequently, Aristophanes partially reworked his play, and it came to us precisely in this second edition.

Somewhat different from the usual carnival type of Aristophanes are his comedies, which pose problems of a non-political, but cultural order. Already the first (not come down to us) comedy by Aristophanes “Feasting” (427) was devoted to the question of the old and new upbringing and portrayed the evil effects of learning in the spirit of the new sophistic fashion. To the same topic, Aristophanes returned to the comedy “Clouds” (423), making fun of sophistry. But “Clouds”, which the author considered to be the most serious of the works he wrote so far, did not succeed with the audience and won the third prize. Subsequently, Aristophanes partially reworked his play, and it came to us precisely in this second edition.

This comedy is so called because its chorus consists of clouds — those new deities that the philosopher Socrates recognizes in place of the old Greek gods. Socrates Aristophanes portrays a sophist, that is, a teacher of false wisdom and the ability to deceive in disputes. The old commoner Strepsiad, entangled in debt because of the wasteful ways of his son Phidippid, heard of the existence of the wise men who know how to make the “weaker stronger”, “wrong right”, and goes to school in the “thinking” Socrates.

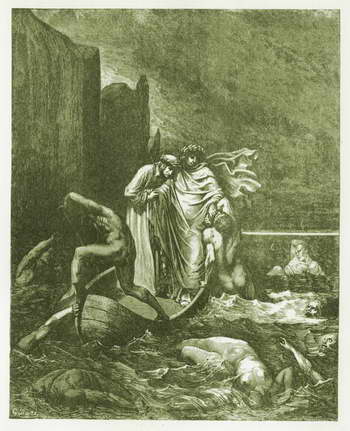

Aristophanes made Socrates a collective caricature of sophistry, attributing to him the theories of various spiritual charlatans, from whom the real Socrates was very far away. Whereas historical Socrates usually spent all his time on Athenian square, the scholarly deceiver of Aristophanes’ Clouds was engaged in absurd research in a “mental” accessible only to initiates; surrounded by faded and skinny students, he hangs in the hanging basket “soars in the air and reflects on the sun.” Socrates takes Strepsiad into the “thought” and performs the rite of “initiation” over it. The pointless and vague wisdom of the sophists is symbolized in the choir of “divine” clouds, the worship of which should henceforth replace the traditional Greek religion. In the future, Aristophanes parodied both the natural science theories of the Ionian philosophers and the new sophistic disciplines, such as grammar.

Strepsiad wants to prove to his numerous creditors by sophisticated tricks that he is not obliged to pay his debts to them. But a straightforward commoner is incapable of perceiving “wisdom” and sends instead of himself to study to Socrates his depraved son Phidippid. Aristophanes shows how before Fidippid they compete in the “agon” (verbal dispute) Truth (“Fair Speech”) and Krivda (“Unfair Speech”). The truth praises the old strict upbringing and its good results for the physical and moral health of citizens. Kryvda protects the freedom of desire. Krivda wins.

Fidippid quickly masters all the necessary tricks, and his father reproves his creditors. But in the further action of the “Clouds” the sonistic art of the son turns against the father. A lover of the old poets Simonides and Aeschylus, Strepsiad did not converge in literary tastes with his son, a fan of Euripides. The dispute turned into a fight, and Fidippid, having beaten the old man, proves to him in a new “agon” that his son has the right to beat his father. Totally entangled Strepsiad is already ready to admit the correctness of this argument, but when Pidippid promises to prove that it is legal to beat mothers, the enraged old man sets fire to the “thought” of Socrates. (According to ancient sources, the current final scene and the contest between Truth and Krivda were introduced by Aristophanes only in the second edition of Clouds.)

In the “Clouds” vividly reflected all the ideological and stylistic features of the works of Aristophanes. The sympathies of the author and the viewer, of course, are entirely on the side of the peasant Strepsiad, and the whole urban education that Aristophanes identifies with sophistry is given a sharp parody, which did not spare even Socrates, the opponent of the sophists, but who also taught new wisdom. Human characters are replaced in the “Clouds” with personified ideas, but their blatant hyperbolism makes the comedy colorful and fun. Since, instead of the former anthropomorphic deities, Greek natural philosophy preached material elements, they are represented here as clouds.

Almost all comedy consists of quarrels, disputes and battle – Aristophanes sees it in them the essence of the widely spread in his era of “enlightening” philosophy.